Keeping Score is an occasional column by Digital Commerce 360 editor at large Don Davis, who has been covering ecommerce since 2007.

I’m finding it hard to be optimistic about the financial future of online retailers, especially those that aspire to be large companies. And it turns out I’m not alone.

Other analysts also see that online-only retailers face stiff headwinds as shopping returns to normal post-pandemic. Consumers are going back into stores, leading to slower online retail growth. In addition, capital is more expensive and the Amazon-driven pressure to offer free and fast shipping is not receding.

There are plenty of online retailers turning in steady profits, but many of them stick to relatively narrow niches and generate repeat income from loyal customers, without spending a lot on new customer acquisition. Pure-play web retailers that have expanded rapidly and gone public are struggling to show steady profits, and investors are bearish on their prospects.

That has implications for startup e-retailers as well as those that already are public companies. Venture capitalists invest in hopes of reaping big rewards, often through a successful IPO. If public online retailers fare poorly on Wall Street, the IPO prospects of other web merchants are poor, and that discourages investors from placing their bets on similar companies.

Online retailers’ stock prices plummet from pandemic peaks

Unfortunately for e-retail entrepreneurs hoping to attract capital, four major online-only retailers that have gone public in the past decade performed poorly on the stock market in the past year. They are: Chewy, Stitch Fix, The RealReal and Wayfair. What’s significant is that these are all successful companies that leverage the reach of the internet in innovative ways.

Chewy and Wayfair showed it’s possible to sell bulky items — pet supplies for Chewy and furniture for Wayfair — effectively online. Stitch Fix provides the kind of personalized fashion advice shoppers expect from their local boutiques, and does it at a scale enabled by the web. And The RealReal took the local consignment shop and turned it into a large, thriving online business.

They all won loyal followings and spots in the Digital Commerce 360 2022 Top 1000 Retailers database, a ranking of North America’s leading retailers and brands by online sales. Wayfair is No. 7, Chewy No. 14, Stitch Fix No. 46 and The RealReal No. 530.

Three of the four did very well during the pandemic as online shopping soared. The exception was The RealReal, which lost ground as health concerns made consumers leery of buying used clothes.

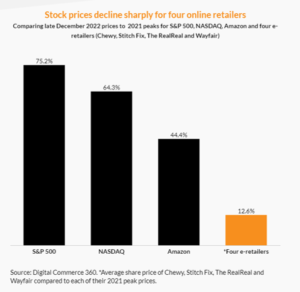

The success of Chewy, Stitch Fix and Wayfair during the COVID-19 lockdowns drove their stock prices in early 2021 to peaks far above their pre-pandemic levels. But it’s been a different story in 2022. Looked at collectively, these four leading online retailers’ stock prices are less than 13% of their 2021 peaks.

To be sure, it’s been a bad year for the stock market, and particularly for technology companies that benefited from the pandemic. The S&P 500, a broad market index, was at only 75.2% of its 2021 peak in late December 2022 and the tech-heavy NASDAQ at 64.3%. Even Amazon.com Inc.’s stock price has fallen to 44.4% of its top 2021 price. But the four online retailers have fallen much further, to an average of 12.6% of their highest price in 2021.

Rising capital costs impact ecommerce companies

It makes sense that the stock prices of companies that went up sharply during the pandemic would fall more sharply when the stock market turns down. But this steep drive in stock price also reflects investor concern that the leading publicly traded online retailers are still not profitable, years after going public.

Not profitable, that is, on a net income basis that counts all expenses, including those that don’t require a company to shell out cash in a given financial period. Startups that raise a lot of money to build their infrastructure and attract new customers often strip out those non-cash items, which include equipment depreciation and awards of stock options.

But those are real expenses. Equipment eventually must be replaced, and depreciation tracks that. Stock options are exercised, if a company’s stock price goes up, which dilutes the value of the company that issued those stocks.

When the economy is booming, investors tend to look for revenue growth and figure profits will come eventually. But that changes when the economic outlook is gloomy.

And that’s the kind of environment we’re in now, says Stuart Rose, a partner at Mirus Capital Advisors, a mid-market investment bank focused on mergers and acquisitions in consumer products and other industries.

“Investors are taking a more cautious approach to investing,” says Rose, who has been involved in buying and selling direct-to-consumer retail companies for decades. “Where in the past it was assumed growth would lead to profitability, investors are requiring profitability now.”

One of the factors making it hard to sell profitably online, Rose says, is merchants that are trying to up with Amazon’s perk of offering free and fast shipping to tens of millions of members of its Amazon Prime program. This perk is largely funded by its highly profitable Amazon Web Services cloud computing business. And rivals’ profit margins are eroded as they seek to offer free or low-cost delivery. Amazon is No. 1 in the Top 1000.

“Amazon almost singlehandedly built the current remote retail environment, which effectively destroyed what was a profitable direct-to-consumer segment,” Rose says. “Low prices, free shipping, two-day or overnight service, were all funded by their fundraising capabilities or the profitability of their other businesses. They ruined the game for hundreds of small to mid-sized businesses.”

Rising interest costs limit growth of online retailers

Besides competition from Amazon, there are several other factors that investors believe will make it hard for many online retailers to grow rapidly in the years ahead, says Eric Roth, managing director, consumer, at private equity firm MidOcean Partners.

He says some larger, publicly traded online retailers took advantage of the combination of low interest rates and surging online demand during the pandemic to borrow money at low costs to attract new customers and to build their technology and logistics infrastructures. But raising money is a lot more expensive now that interest rates have risen significantly, he says.

Plus, growth is challenging for e-retailers and direct-to-consumer brands that offer a limited range of products.

“How many different ways can you make a shoe, a pair of pants or a shirt that you don’t have to tuck in?” Roth says. “Some of these companies have run out of new ideas.”

How can online retailers compete successfully?

That’s not to say there is no future for online retailers, say experts like Roth and Rose.

E-retailers have to keep innovating and introducing new products that capture consumers’ attention, Roth says. He points to Nike as an example of a brand that has consistently out-innovated its rivals. But, he notes, few online retailers have the research and development resources of Nike (No. 10 in the Top 1000).

Opening stores is another way to grow, Roth says. In this, he agrees with analysts at Forrester Research who say direct-to-consumer brands born on the web will only survive if they open their own physical stores or sell wholesale to store-based retailers.

Roth notes some born-on-the-web brands like Bonobos have grown by opening stores without taking on a lot of inventory risk: Consumers can see and try on clothes in the stores and then their selections are shipped from warehouses to their homes.

“People can treasure hunt in the store, but it’s still an inventory-light model because they ship products to you,” he says. “In-store, people can look for their size and the features they want, the way people still want to do.”

The other path to success for online retailers would be to sell more to the customers they acquired during the pandemic. But e-retailers haven’t yet shown they can do that.

“At least the market is not giving them credit for it,” Roth says.

Rose says online retailers should jettison money-losing parts of their business.

“I have found that even unprofitable businesses have a subset of the total business that is profitable,” he says. E-retailers that are struggling, he says, “must find that part of the business that is profitable and discard the rest. They will end up with a smaller and healthier business.”

Mid-tier online retailers compete with expertise and service

Many of the online retailers that have been around the longest have survived by simply not trying to grow beyond their narrow, but profitable, niche. In fact, the retailers ranked in the 2022 Digital Commerce 360 Next 1000, those ranked from 1001 to 2000 in online sales, increased their collective web revenue 22.8% in 2021 over 2020. That exceeded the 15.7% growth of the larger Top 1000 retailers and the 14.4% increase in U.S. online retail sales.

Often, mid-tier online retailers survive by offering unique products and real expertise in their fields. Examples include educational playthings merchant Fat Brain Toys (No. 709), South American apparel importer Peruvian Connection (No. 686) and sewing supplies retailer Lion Brand Yarn (No. 1002 in the Next 1000). Note that these are all private companies that don’t need to show the kind of continuous growth that brings success on Wall Street.

And sometimes online retailers succeed with superior service, offered year in and year out, earning them loyal customers who come back to buy, even if they don’t offer the lowest prices.

A prime example is another privately held company, Crutchfield (No. 232 in the Top 1000), which began in 1974 as a catalog selling car stereo equipment and now offers a full range of consumer electronics. My good friend Brian lives in Charlottesville, Virginia, where Crutchfield is based and operates a physical store, and his recent experience shows how to build customer lifetime value.

Brian was looking for a new TV and a sound system to go with it. His first stop was the Crutchfield store where he found knowledgeable associates who spent time showing him a variety of products and answering his questions. He then went to Best Buy, where he couldn’t find an associate in the TV section to help him, and quickly left.

Then he went online, where he found better prices than Crutchfield for the TV he wanted, and a 50% off sale on a compatible sound system at Costco.com. He went back to Crutchfield where the same associate he had spoken with previously helped him again, and pretty much matched the price of the TV. But when he heard how much Costco was asking for the sound equipment, the associate said, “Brian, grab it.”

But Brian had a concern: Would Crutchfield install both the TV and the sound system, even though he bought the stereo equipment elsewhere, he asked. “No problem,” the Crutchfield employee said. And so they did, for a reasonable $150.

Brian is thrilled with his new TV setup. And Crutchfield not only got part of his business this time, but it also earned the right to be his first stop next time he’s looking for electronic equipment.

That’s how retailers earn consumers’ trust and stay in business, regardless of interest rates or stock market fluctuations.

Recent Comments